“I never like to draw. I’m not a planner. I’m a very intuitive person.”

Gabrielle Venguer

It’s been minutes since I sat down to interview the Mexico City-born designer Gabrielle Venguer, and already it feels that she’s grazed something vital. Turning the laptop camera away from herself, she shows me the inside of her atelier and by-appointment storefront in the heart of Mexico City’s La Condesa. Between sewing machines and worktables, the far wall of the quaint sunlit space is practically impastoed in layers of photography and research––Gio Ponti’s Taranto Cathedral, a white marble Capitoline Venus sculpture, slick 1972 leather styles from classic rock-and-rollers like Mick Jagger and Jimi Hendrix. Other newer reference materials are still waiting to be metabolized into her designs. She turns the camera back. “Everyone else in the studios at school, people were drawing and they knew exactly how many looks they were going to have, and they knew what was going to work and what wasn’t. And I never knew. I still don’t know how many looks I’m doing in a collection. I’d so much rather experiment.”

For Venguer, who returned to Mexico City just before the 2020 pandemic, and after four years split between prestigious London graduate programs at Central Saint Martins and the Royal College of Art, this embrace of intuition and experimentation is, if not a whole design philosophy, then an indispensable element of her process. Alongside a tight-knit team of local artisans and craftspeople, she’s been producing limited and one-off designs in small capsule collections, working from the ground up in a slow, sensitive approach to production and materiality that utilizes upcycling, organic batch-dyes, and traditional handicrafts—alongside what she best describes as a sensitivity to “balance”: “it’s the common thread that goes through it all. Even if it’s changing radically from collection to collection, I can see the throughlines in the way I work with materials and colors, and the balance I try to achieve. And at the end of the day, the fabrics I use, I don’t even try to choose them. It’s that I’m drawn to the colors, I’m drawn to the materiality, to the shininess, the roughness. It has to do with my own sense.”

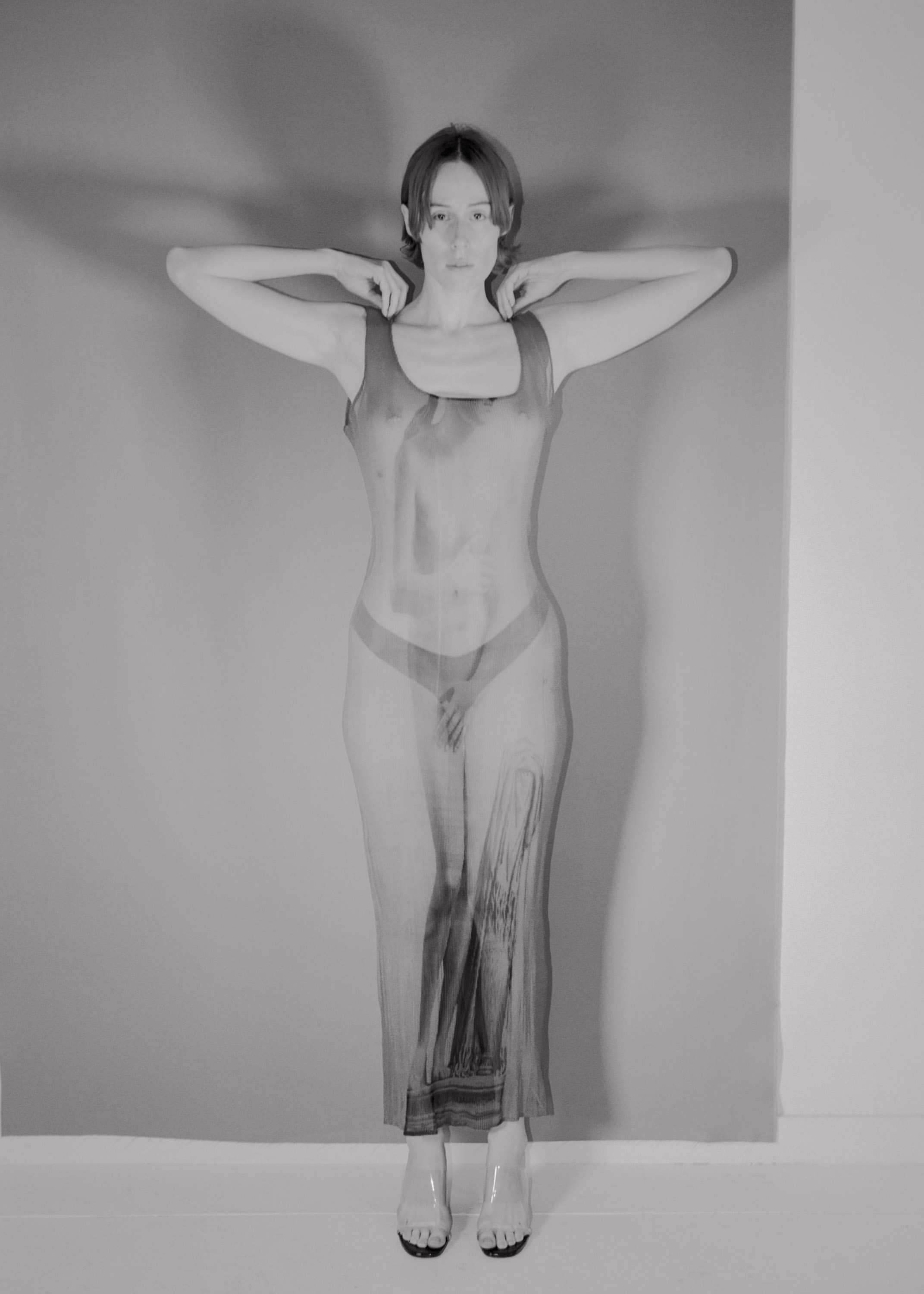

Most recently, Venguer has teamed up with Ecuadorian-born, Brooklyn-based artist and photographer Andrés Altamirano, whose own lens tends toward an unmistakable luminosity. Together, they took designs from her most recent collection to the studio and the streets of New York. In one look, a removable green fur collar and jacket is paired with a leather miniskirt featuring the slinky eyelet lacing detail for which Venguer has increasingly become known. In another, the same Capitoline Venus is digitally printed on a red sleeveless midi-dress, creating a sort of trompe l’oeil “nude” overlay. Venguer moves nonchalantly between leather and fur, knits and transparent silks, experimental dye effects and bold color-blocked styling. Everything’s on the table for her, and nothing feels overdetermined. There’s a fabulous, fringe-trimmed skirt set that I can’t help but ask about. Venguer laughs. “Cruella. It’s very Cruella. At the time I was exploring optical illusions and illusionistic knitwear, so the squares in the pattern appear and disappear depending on the wearer’s movement. It’s a hand knitting technique, a pretty modern one, and I took it to a knit shop run by mostly older women. They flipped out at first, asking “how are we going to make that?” But of course they’re experts in hand knitting, so they understood quickly. So yes, those pieces are handknit by grandmothers.”

We get to talking about her return to Mexico City.

Gabrielle Venguer: I came back to Mexico right before the pandemic started, mostly because I didn’t want to be away from my family for so long. So I came back, but I thought––what am I doing in Mexico if I was in London? London has the best schools and the best fashion, and no one cares about Mexico in a way. And instead I was surprised to see so many people with this urge to create and to collaborate, to have our own voice in Latin America. It was amazing to return and feel that there’s something really happening here, that now is the right time to be in my own country.

I started my label around the same time. I was experimenting a lot, working with a stylist at the time. We were both wearing a mask and gloves, going back and forth deciding “this doesn’t work, this works.” I would give her my stuff and she’d photograph it. And it just started very organically. And it’s continued to develop very organically. I don’t trust any process in my life as much as I trust this one, because when I’m ready for the next stage, it’s been that the door opens and I know where to go.

Wes Hardin: You mentioned earlier that before London, your design education actually started in Mexico, in textile design specifically. What was the initial draw to a textile discipline as opposed to, say, womenswear or more general design?

GV: My mother is a painter and a sculptor, and I wanted to choose something that felt like my own medium. Growing up, I always worked with textiles at home. I used to do all kinds of painting and embroidery in textiles since I was young. And I thought at the time it was going to give me an introduction to where I wanted to go.

WH: In some ways that’s really the right place to start. I wonder that oftentimes design can stray far away from working at the level of the building blocks, the level of the elements, the fibers, really basic stuff from the earth that forms larger composites. I suppose I’m wondering if you could tell me about your approach to material in this vein, the building blocks of clothes and how they inform your design, or vice versa?

GV: Absolutely. I’ve found that if I play with material, it’s like a conversation that’s starting to emerge. I do a lot of research with dying materials, with breaking, with tearing, with weaving. For my type of brain, I find that if I create or imagine my textiles from scratch, the world of possibilities is much bigger. And it’s always a bit like a puzzle.

I remember I went to my critic at school once, and they told me, “oh, this dress is the best thing you’ve done, but it still needs more refinement.” And I told the tutor, “but I spoke with the dress, I spoke with it, I knew what it needed in each part.” And she told me, “well, speak longer.” And it was just like that, a way of understanding what it needs and when it fits. It’s all about equilibrium in a way. When I’m creating a new collection, I put all the things I’m working on and the materials I’m using on a rack, and I ask, what is it missing? It needs a punch, or it needs fluidity. It’s a bit like a canvas, where you need to have a balance of colors and shapes and textures and transparencies and depths. So I like to paint the collection in real time and not decide beforehand.

WH: Where do you find yourself looking when you’re not, I suppose, when you’re not talking to the dress, having a conversation with the dress? What else are you conversing with?

GV: At the moment, I’m constantly looking through architecture. My partner is an architect, and I’ve started traveling hours just to see a building, four hours in a car just to go to a church. You go see a Pesce house in the middle of nowhere, and you’re just like, wow, that materiality. It’s as though all these spaces have such strong personalities, a Ponti church that looks almost alien, or a Carlo Mollino theater where I can see the way that he uses velvet, and contrasts it with a kind of origami in the ceiling.

They’re like these worlds, and I think it’s the most interesting and also the hardest thing for a designer or an artist to have their own world, that you continue to construct every day with time and intention. I remember at CSM, my very first critic told me I had no identity, and I cried for hours. I don’t have an identity. I don’t know what I like. It was very interesting to sit down in the library and pick all these books and start to get to know myself. Oh, I like this color, I’m going to photocopy it. Oh, I like this texture, I’m going to photocopy it. And I started building a library. And now that library is everywhere in my brain, in my mind.

Words Wes Hardin

–