Constructed from subcontinent fabrics, the Ceylon Shirt is a cotton short sleeve shirt with a revere collar. Features include flat felled seam construction, mock placket sleeve finish and natural calico reinforcement at facing and collar, with two large patch pockets at the base. Hand stamped at inside collar documenting the article code, production year and size. Limited to fifteen shirts in total.

—

Araly

This is a collection of shirts that remind me of a time in Araly, a small village in the Northern tip of Sri Lanka.

My first and only trip to Araly was with Ammamma & Pata in December 2012. Araly neighbours Jaffna, a Northern village that was the epicentre for a brutal Civil War that rocked the country for 30 years. It took four different modes of transport across two days to get there from Colombo, a stretch of under 400km, that’s how literally bombarded the roads were from South to North.

It was hot, and I was there in monsoon season. I’d never seen rain like monsoon rain, falling to the ground dramatically like a show curtain, its sound like a never-ending applause. Between patches of lush rice paddy fields, bicycle riders would neatly prop up umbrellas with one hand while they shimmy along the most uneven of dirt roads, the heat heavy in the air. On the corners of each road would sit stationed army troops, their presence heavy like the humidity.

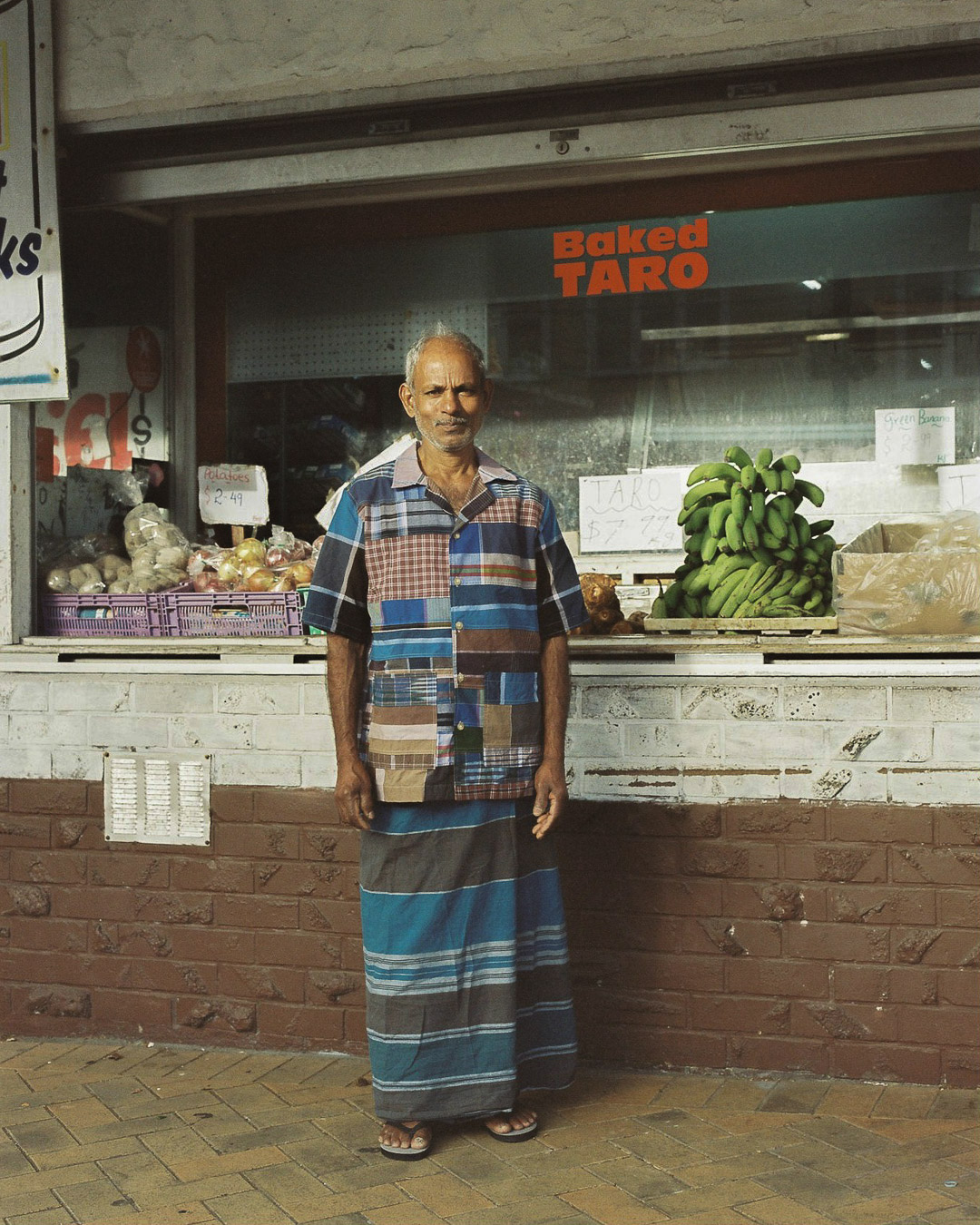

To combat the hot climate, the men in Araly would wear a cotton saaram knotted around their waist, an array of multicoloured plaid checks flowing through the village. They would sit naively in the shade, sipping sweetened tea with their saraam tucked between their legs, flashing a toothy grin as you walk past, teeth red from a life chewing betel quid. Labourers would wear them as they plough rice paddy fields or wading through water to collect fishing nets, the bottom neatly tucked up again over the top to free up the knees for work. The slow, monotonous beating heart of Araly and their community epitomised with the ubiquitous saaram, a subcontinent blue collar, resilient, unassuming and able to withstand the harshest of elements.

~

The temple in Araly was situated in the middle of the village, my Pata and his family had contributed money to it being built. I remember rounding the corner to see it for the first time, built from so much stone and gold it practically glowed around ramshackle houses. The smell of sandalwood and Tēvārams sung by priests and devotees mixing in the air, offerings of fresh fruit and cāppātu laying untouched at the base of deities. Women were draped in cotton or silk sarees with heavy gold thali’s glistening around their necks, a matrimonial weight of surety. The men now dressed in white head to toe, having put down their tools, a white linen veshti in place for a saaram sitting around their waist. The dress at the temple was a strange mix of opulence & uniformity, for a society steeped in hierarchical caste systems it seemed an oddly egalitarian way to dress. And what appeared to be an unnerving sense of irony where people staved off dengue fever and lived in abject poverty within the village, seemed only obvious to me. I was witness to how the temple seemed to commandeer a level of abstract divinity to those living in Araly, unsure if they were richer or poorer for it.

~

The Ramayana Hindu epic retells the story between King Ravana, demon-king of Lanka and Indian god Rama. King Ravana abducts Rama’s wife Sita, holding her captive in his kingdom in Lanka in the town Lankapura. Rama recruits the Monkey-God Hanuman to retrieve Sita, who leaps across the Indian Ocean through the mouth of Surasa, a sea monster, on the way to the island of Lanka. Having shrunk to the size of a mouse, he finds her held captive in an ashok grove near Ravana’s palace. He brings good news back to Rama in Kishkindha of Sita still being alive, not before setting fire to Lankapura with his tail alight, wearing a pancha around his waist, leaping back across the Indian Ocean with Lanka burning in the distance.

~

I recall being in Araly imagining a life that could have been so easily mine. Reflections of myself in the village, a saraam wrapped around my waist, teeth red pleasantly absent-minded on how to fill the days. I would imagine a life comprised of rolling blackouts and enviable simplicity, this by nature the very life my Pata was brought up to leave. I think of my Pata, a journeyman pensive to his very last days, holding a love so pure for those in Araly that had helped him along his way. My lasting memory of him sitting in his cane reading chair devouring old Tamil literature, fresh from an evening bath wearing only a saraam as he prepared for bed. ‘I’m not sure how this happened, I used to be so thin’, he says slapping his fat belly with some sort of misguided belief, a house crawling with grandchildren.

— Prakashan Sritharan